August 24, 2019

Process of Elimination destructive feedback you can expect for any credible funding idea

An old friend from the early days of Node.js, Feross Aboukhadijeh, tried a new funding approach this week. He added a script, funding, to run after every installation of standard, his wildly popular style checker for JavaScript. At launch, funding showed curses-style terminal ads for two companies, Linode and LogRocket, who paid Feross for the privilege. Feross used the money to help him release standard 14.0.0.

This is not the first way Feross has tried to fund his open work, and I could not be more supportive of his experiments. I don’t think ads are the best model for developer funding, and I hope they don’t catch on as the go-to solution. But I’d rather be wrong and see developers funded than right and see them continue to struggle and fall to back to writing closed, one-off code. Even if open software ends up looking like NASCAR.

That said, Feross’ choice of ads was not my immediate cause for concern.

I have seen many open developers try new ways to fund their work. I know what comes next. I know the toll the harassment takes. And harassment is what it is. Nothing more. Nothing less. Nothing else.

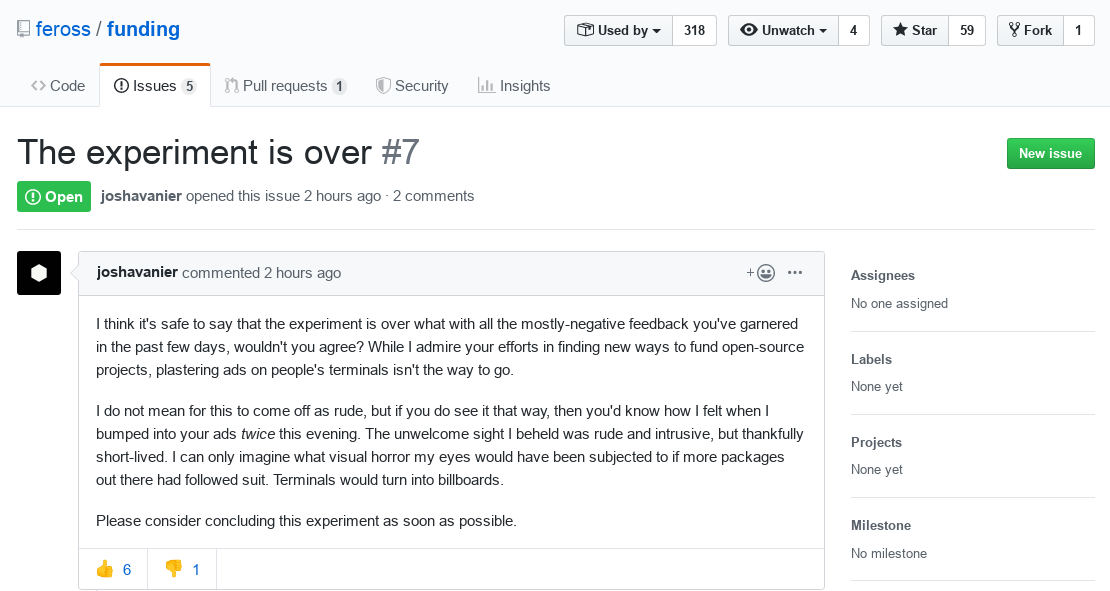

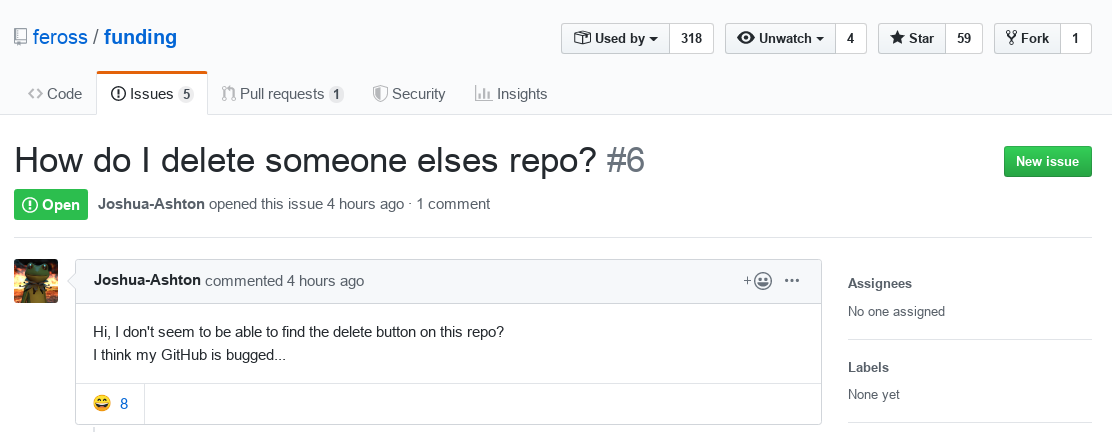

This is normal:

Actually, that’s relatively tame. But these were relatively early. In time, it will get worse. The brigade will grow.

Often, it happens all at once, in a rush, after the story reaches critical Hacker News velocity:

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=20786981

Many of the comments we’ll read there, on Twitter, on GitHub, and God knows where else, will fall into familiar patterns. We see them every time.

Here we go again.

“Anything But This”

A lot of comments will start with loud and proud professions of support for the idea of funding maintainers, and then condemn whatever specific way the particular maintainer has actually attempted to get funded. Because the approach is stupid. Or shameless. Or unethical. Or hopeless. And so on.

Feross tried ads in terminal messages, so we read that he should have put them in README. When folks started putting ads in README, we read that they should have put them in documentation, or on a website.

Paying a developer to put an ad where nobody will see it isn’t constructive business advice. It’s asking either to deceive an advertiser or to pretend that donations are a business model, by papering them like insertion orders.

“How About the Obvious?”

In the rare comment that offers an alternative, the approach will likely be a well marketed one that the maintainer has already tried, without success, or one with a dubious track record. Nine times out of ten, the approach boils down to begging for donations online.

Track records often look very different to maintainers who’ve tried, as opposed to those reading the marketing pages from service providers. This is particularly true of situations where outliers get unusually great attention, on top of unusually great dollars.

Yes, Feross was already on Patreon. For quite some time, actually.

“Anyone But Me”

Some otherwise more constructive comments will advocate alternative approaches that shift the burden—payment, attention, mere awkwardness in being made to see a fellow dev in need—somewhere else. Anywhere else. Just not on other developers.

A favorite target is “companies”, especially “big companies”. But not, apparently, the companies paying many of the commenters to do their work. Not employees at companies who are paid, in part, for delivering the value of open software they found, rather than closed software they themselves must write and maintain.

Approaches that do focus on corporate payments receive a different battery of criticism. Companies won’t pay. The deals are too small. Procurement takes forever. You need a big sales team. All the myriad ways that companies say “anyone but me”, in their own special corporate way.

“Nothing To It”

Comments will rush to belittle the maintainer’s software as trivial. When that reads earnest, it’s often a badge of honor: The developer has hidden the internal complexity of their work effectively. They have made it seem simple. Which explains how this response comes up pretty much no matter what kind of software is involved, from small libraries to complete applications.

These comments frequently take an oddly narrow view of time, as well. They’ll assess a project by a single GitHub flyby, regarding only current functionality, and proclaiming the whole easy to replace. The effect is much the same as the “I built X in a weekend!” posts we see online from time to time, except nothing actually gets built.

I suppose for highly stable software, for a highly stable environment, in a highly stable programming language, targeting a highly stable machine architecture, and so on, a clean-room mentality might just fit. But those are rare exceptions. Many of the maintainers suffering for lack of funding are feeling the burn precisely because the ongoing burdens of maintenance, planning, and compatibility add up on them, over and above feature implementation. Many develop unique reputations and user relationships that uniquely qualify them to continue leading development as a whole.

Forking those efforts, without their maintainers, in a fleeting spurt of self-righteous productivity, exactly misses the point. I don’t need or want a fork of standard version 13. I want Feross, the guy from my development community who ended up diving deep into JavaScript style and linting for five years, to keep standard evergreen, so my projects can continue to adopt and rely upon it. I don’t need a clone of standard. I need a clone of Feross.

The homework that entails is exactly the homework flyby clone-fork-and-burn advocates do not see. If they did, the task wouldn’t seem so easy nor the maintainer so fungible. If the maintainer themself could have seen it going in, they may not have signed up.

“Don’t Go There”

If we took all these shots to heart, we’d end up with nothing to do and nowhere to go, having eliminated all options. Somebody would veto everything.

If you like the status quo, that’s great. Contributors give, and expect to give more. Consumers take, and expect to take more. Up to a certain point, it can still be good to be an open source producer. Until it’s not. But it’s always great to be an open source consumer. It is only getting better. Unless word gets round that the rational approach to open is doing a little bit, to make a few resume points, stop, land a paid gig, and leech.

Some will skip right to this point, and take a hard position that money and open source simply don’t mix, shouldn’t mix, or cannot mix. The upshot? Go get a job writing closed code, or doing something else. These responses attack the legitimacy of the problem—finding a way to fund open developers so they can do more open source work—itself. If there’s no problem, what’s the problem?

Money was all over open source before it was “open source”.

But mostly unfairness.